There is a place I can’t visit anymore except perhaps by writing about it.

Saturday morning- we set off in our black Hindustan on the 30 mile trip from Thalassery to Kunnoth. It is a weekly routine that lasts from the beginning of my memory until I was nine. Father drives, mother sits in the front, a child or two squeezed in between them. Assorted other siblings sit at the back, pulling my ears, or occasionally pinching me, just to pass time.

We stop at Koothuparambu to visit my uncle, father’s brother. The brothers tell each other little anecdotes, their trademark laughter sounds like they are having wheezing fits. Father’s grey green eyes twinkle in delight and his face reddens as stuffed deer-heads on the wall stare down at us in indulgence. Their disproportionately large antlers mesmerise me with their elegant symmetry.

The yellow milestones on the side of the road, the seven white furlong markers within each mile, the verdant moss and blood red hibiscus flash by as we resume our journey. Father stops the car after a few miles and gives a silver rupee to Bhaskaran who waits by the roadside in expectation of his weekly gift. His lifeless limbs, afflicted by Polio, are contorted in impossible directions. He smiles and waves goodbye dragging himself off the tarmac.

The next stop is Mattannur, home of Kuttiraman the child who spent his life in servitude to our family.

Kuttiraman was found standing at the gate when my brothers returned from school. This undernourished, semi-starved child wearing only a red loincloth was hired to look after me. I was almost the same size as him though several years his junior. Kuttiraman grew up with us, finally emigrating to America and returning to Mattannur to become a mini landowner himself. His story needs more telling for his is also the story of the velvet revolution of Kerala, where the world’s first Marxist government was democratically elected.

No American dream though for poor crippled Bhaskaran. One Saturday, the last that I remember, a driver drives us to Kunnoth. Father is dozing and Bhaskaran, having recognised our car, beams in expectation of his rupee but the driver does not stop. I remember looking at him through the rear windscreen. His look of baffled disappointment still haunts me. The resentment of a whole people is distilled in his eyes. Why didn’t I wake up father? Why do I still feel as if it was all my fault?

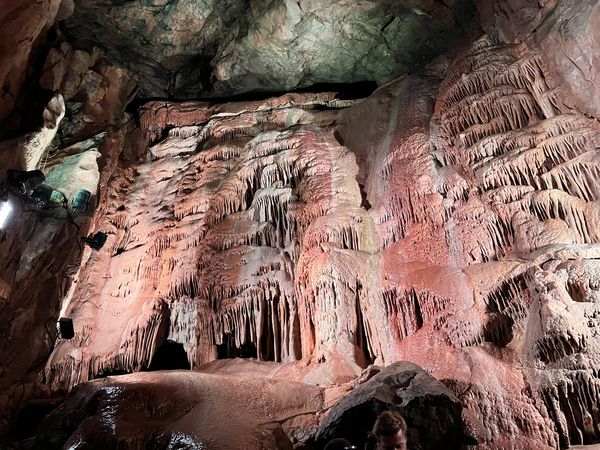

Onwards from Mattanur and across the bridge over the Iritty river. If you go there today, you will see a placid lake, the river having been dammed many years ago. But, to me it is alive: a wild galloping beast, furious, snorting iridescent sprays on to moss laden banks, raging ahead in tumescent turbulence as giant uprooted trees, like flotsam, cling to its deep silver mane. We cross the bridge and leave the roiling river behind.

We arrive at Kunnoth and park our car by the stream that bisects our land: the stream where we catch tiny flame coloured fish with a Kerala thorthu (a porous woven towel) and gently release them, the stream on the banks of which bushes of pineapple and sugar cane proudly flaunt their fecundity. In contrast, carpets of tremulous touch-me-nots close and withdraw when we trample them under our wellingtons.

Wellingtons are mandatory, even in the blazing hot summer. It is protection against venomous snakes. I see more of them in father’s vivid descriptions and never really in flesh. But stories about snakes are enough to make us keep our boots on. We tread on dead leaves and abandoned ant hills without fear. We are told never to poke a stick into any hole in the ground or on earth mounds because even a newly hatched cobra could slither up the stick and kill us faster than we could withdraw the stick or drop it. Such is the fear of snakes that a harmless water snake frightened the hell out of us. But serpents are part of every story and our Eden was no different.

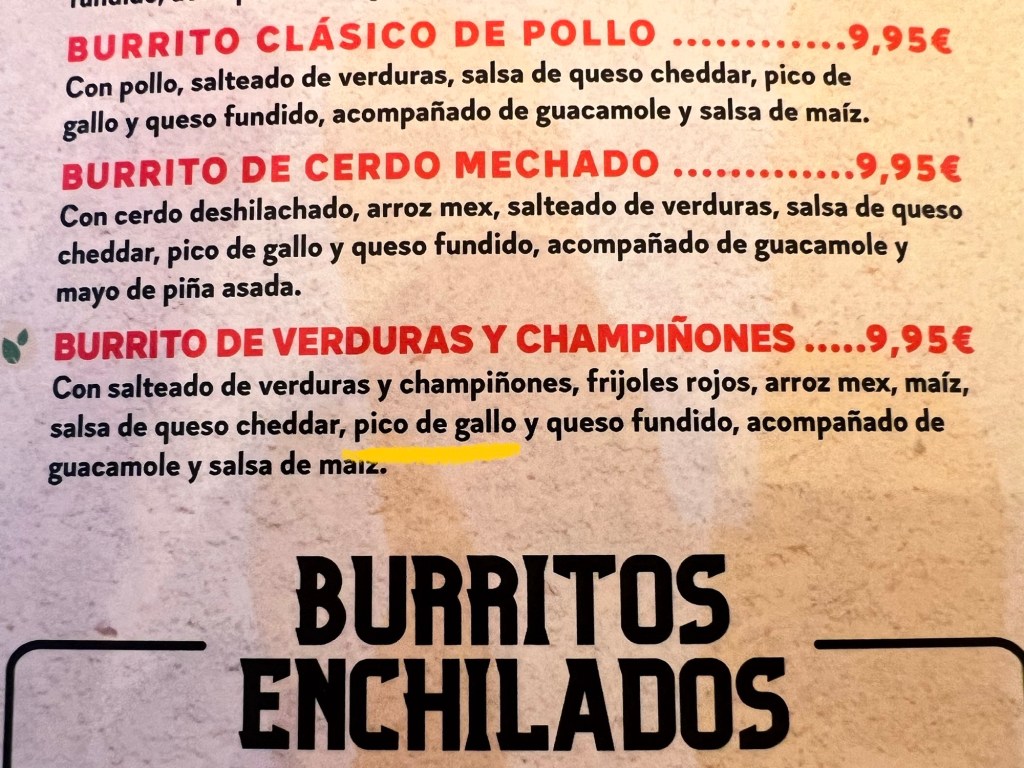

The tenants and labourers wait for father to pay their weekly wages. We slip away to cavort in the stream and climb smooth guava trees. We bite through the thick skin of sugar cane to relish its fibrous sweetness and finally return to the cool veranda of our thatched roof house. Banana leaves are placed on a ring of soft bark of the plantain tree and ripe jackfruit leaves stitched into conical shapes with the spine of coconut fronds, serve as spoons. Naranettan, manager and maitre-de, serves us hot rice gruel with delicious tapioca stew, whole black lentils and a melange of tender jackfruit with freshly grated coconut, and spicy pickles. A dollop of ghee from the milk of our own cows, couple of sweet little bananas, a piece of jaggery, and we are ready to go out again. Mother forces us to rest a while before we sneak out. All the used leaves and spoons are thrown into a huge compost pit behind the house. We rarely see or use plastic.

In the evening, father takes us along on his inspection of the farm. We are accompanied by a few tenants and Naranettan. People seek father’s attention invariably asking for his help in what seem to us as trivial matters. A woman needs a few rupees to buy a cow, someone wants to dig a small channel to divert water from our stream to their tenured land, someone else wants a piece of land to cultivate some grains. I cannot remember the details or if the decisions were in their favour, but I see most of them go away with a smile.

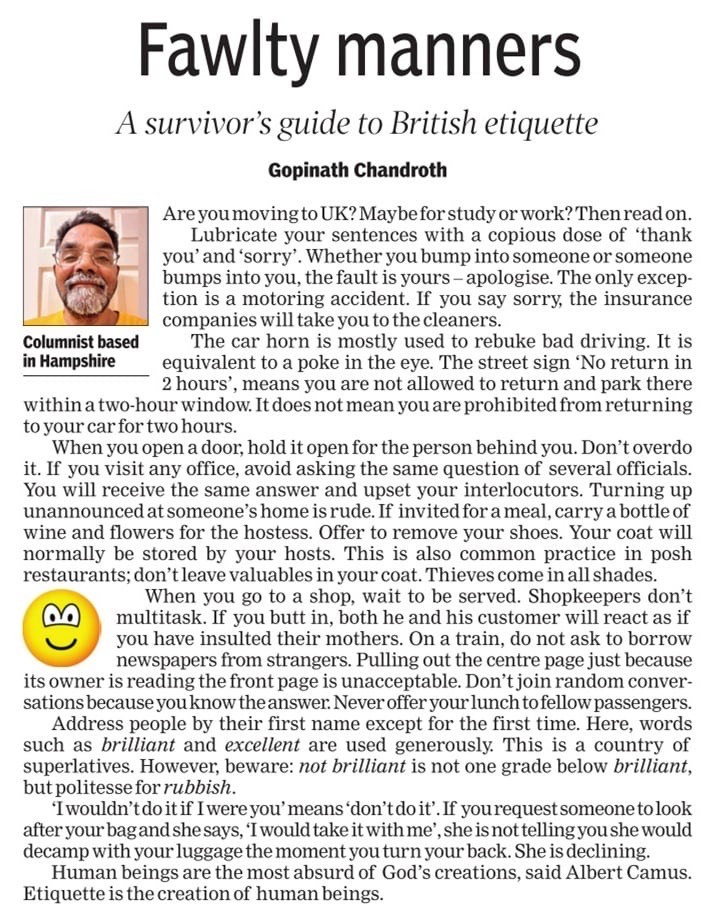

At dusk father sits on an easy chair on the verandah and tenants and others congregate in the compound below. The men stand ever so slightly stooped as a mark of supplicant respect, holding their customary thorthu turbans in their hands. The women stand to one side whispering softly among themselves. Father, his socialist disposition in conflict with his feudal authority, speaks kindly to them and I imagine metes out justice where required. He does not raise his voice at the tenants or even speak harshly to them. Or do we only remember what we want to and forget the harsher moments? I narrate this as I remember. The concepts of feudalism and the inequities of disproportionate land ownership do not register in my six year old mind. But there is a restive unease that makes me slightly uncomfortable.

The weeks roll into months and years. Father shifts his law practice to the High Court in Kochi and our visits to Kunnoth become infrequent. Naranettan leaves under a cloud and is replaced by Jaleel, the brave-heart who chopped a deadly King Cobra in two with his machete as it stood on its tail hissing at him. Or so the story went. Kerala enforces the Land Reforms Act, one of the two Indian states that implements the federal Act. Most of our tenants become landowners. Kerala transforms from a poverty-stricken caste ridden plutocracy to a thriving egalitarian socialist state. The people of Kerala stand erect with their thorthu proudly crowning their heads.

On a journey from Thalassery to Bangalore, you will pass Kunnoth on your left just before your car starts climbing up the Western Ghats. If you recognise the Eden of my childhood, stop your car and peep inside. If nothing else, you will see the shy touch-me nots. Touch them, but gently, on my behalf.