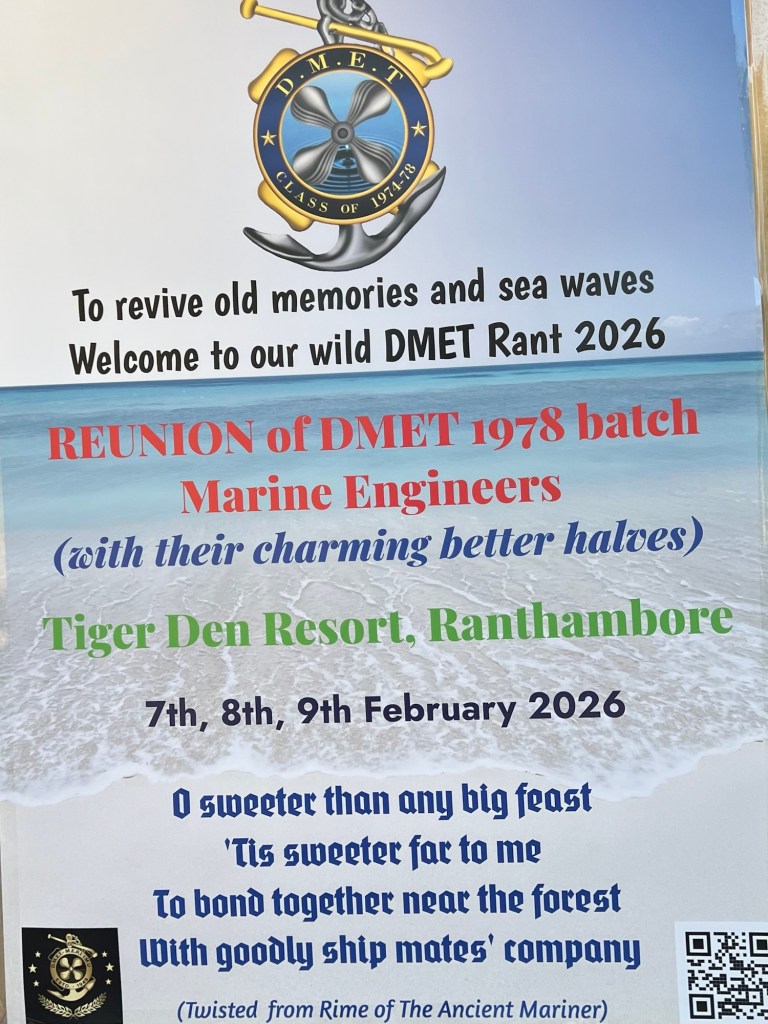

It is hard to put a finger on it: the intensity of this curious feeling – this affection and camaraderie for our batchmates, friends of fifty years and more. Perhaps the symptoms are easier to articulate – the childlike excitement that makes us wake up too early or go to bed too late, as if every extra minute spent sleeping is time lost, time that could be spent with our brothers.

And so, in the thirty-six hours that we spent together, we laughed incessantly, talked, reminisced, and sang. We became ourselves – uninhibited, silly, genuine. We shed the years that made us old. We were rejuvenated and became young again.

We ate together, drank tea by the poolside in the early hours and ended our days in song, warmed by the heat of the bonfire and the cheer of our favourite tipple. Our stock of tales did not deplete as every incident we remembered found others that lay deeper in memory, and our recollections traversed our lives like the widespread roots of an ancient tree.

We went to see tigers in the forests of Ranthambore without much hope of seeing one. Yet we withstood the jolt of the canter that took us deep inside the jungle because we knew we would enjoy the drive with our friends and relish the banter, tiger or no tiger. But luck favours the good-spirited and we saw not one but three tigers at close range.

The guide did his best to prevent us from taking photographs. “Ma’am, no, sir, no,” the poor man entreated us, trying to enforce the latest rule against using a mobile phone, but only a regular camera to take photos of the wildlife. The logic of the new law was as obscure as the aphorisms in the Rig Veda. So, as you can only do in India, we ignored the rules and thumped our noses at the mindless diktat. We captured images of crocodiles, deer, monkeys and tigers. The azure sky and the placid lakes with the ruins of the Ranthambore fort up on the mountain framed the images in our memories better than any camera could capture them.

The Anthakshari by the bonfire was something else as our wives outdid us in their quick-witted responses, winning the contest hands down. Two days that seemed like two seconds. Time had a strange way of compressing itself when we were with the friends of our youth.

The food was par excellence, except perhaps for the desserts. Rasagulla and ice cream pretending to be rasmalai, pakoras that emerged only after stern requests – but we didn’t go there to eat. The food was enough to sustain us. The bonhomie carried beyond our group, infecting other guests, some of whom joined in and sang with us – in German! The other tourists didn’t object to our mirth; how could they? Perhaps they carried away with them lessons about beating old age with the drug of fraternal love.

And so we finally bid each other goodbye. The typical Indian goodbye, someone remarked. Yes, it was typical — and something more. It was lingering, never-ending, hugs and kisses and the tears held back but always threatening to burst forth. How wonderful those two days were, how uplifting. We departed with promises of returning soon.